I went looking for some new SD cards for an upcoming trip, and was a bit horrified by the criteria used by reviewers of memory cards. One of the most popular was the "frame burst rate."

When a digital camera records an image, it temporarily holds it in a buffer where certain software might be applied (as when you save JPEG files instead of RAW files), and then writes the image out to the memory card. The "burst rate" of a digital camera is the number of consecutive images that can be made before a bottleneck gets encountered and slows the camera down enough to prevent an image being recorded when the shutter button is pushed. There are many hardware bottlenecks, but theoretically, the one most likely to be encountered by the photographer is the speed at which the memory card can accept data.

I understand when manufacturers fluff up irrelevant numbers (like the gigahertz of computer processors) in an effort to make their products look better. But when photography writers look to criteria like "frame burst rate," something's very rotten in the state of the medium.

Still photography is just that—still. A DSLR or a mirrorless body is a device for making one image at a time. Still photography is about single moments. It's about the photographer orienting to the situation and the event, and choosing which moment will best capture the feeling of that moment. If the artist wants to make more than one image at a time, there's a solution for that: a video camera.

For a photographer's purpose, there are only a few technical considerations that matter:

- Longevity matters. Memory cards can get heavy use, and the quality of the components is not insignicicant. You want a card from a reputable manufacturer that will hold up over time. A lifetime warranty is a good indicator of quality manufacturing. But so is brand.

- Getting past the camera's buffer matters. The hardware of the camera has limitations and requirements, so keeping to the manufacturer's guidelines will make the camera perform at its best. The camera manual has those details, or you can find them online.

But if "frame burst rate" matters, then you need to rethink whether you're a photographer.

And before you think "oh, but sports! That's where it matters!" it doesn't. Sports is no different than any other kind of photography, and in the great history of excellent sports photography, it has always been about the moment. Spraying and praying doesn't make good images, no matter how fast the action. The vast majority of great sports images were made on film, and with motor drives that topped out at 5 frames per second. Even then, no photographer I knew ever shot that fast for two reasons: there was a risk of ripping the sprockets; and you didn't want to use up your precious few frames of film that fast.

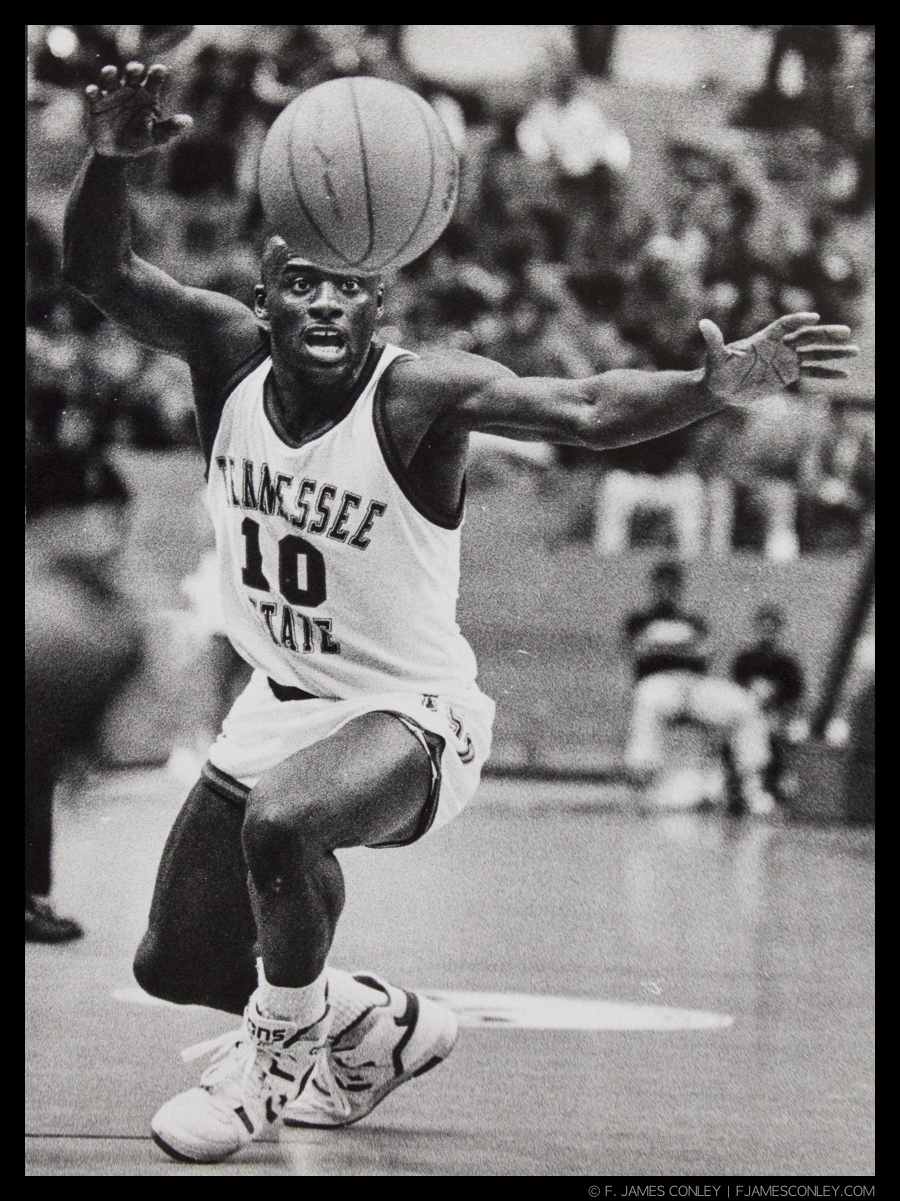

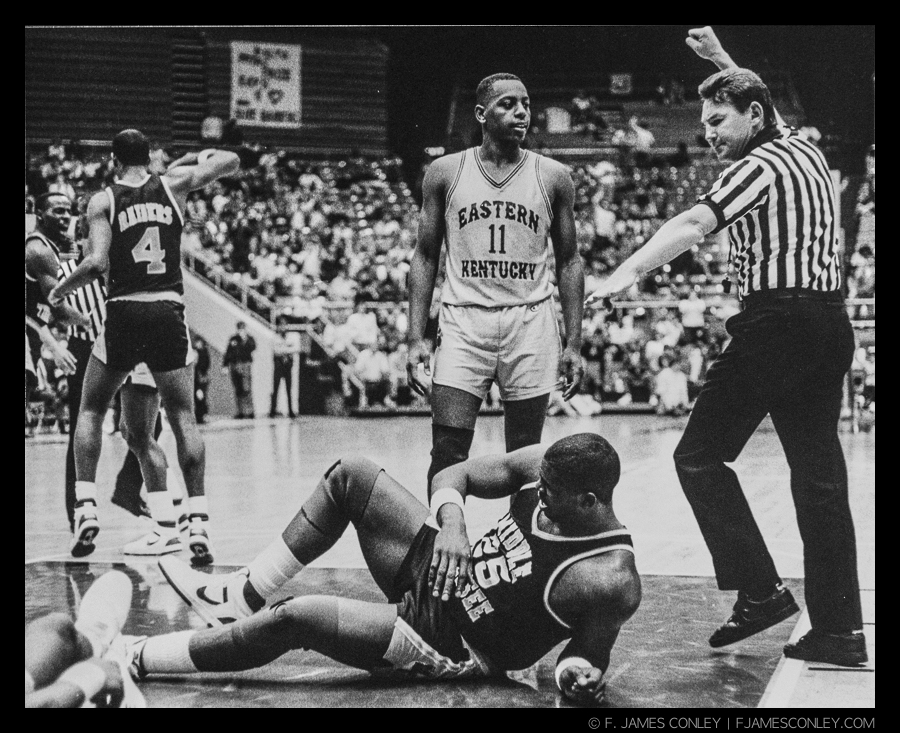

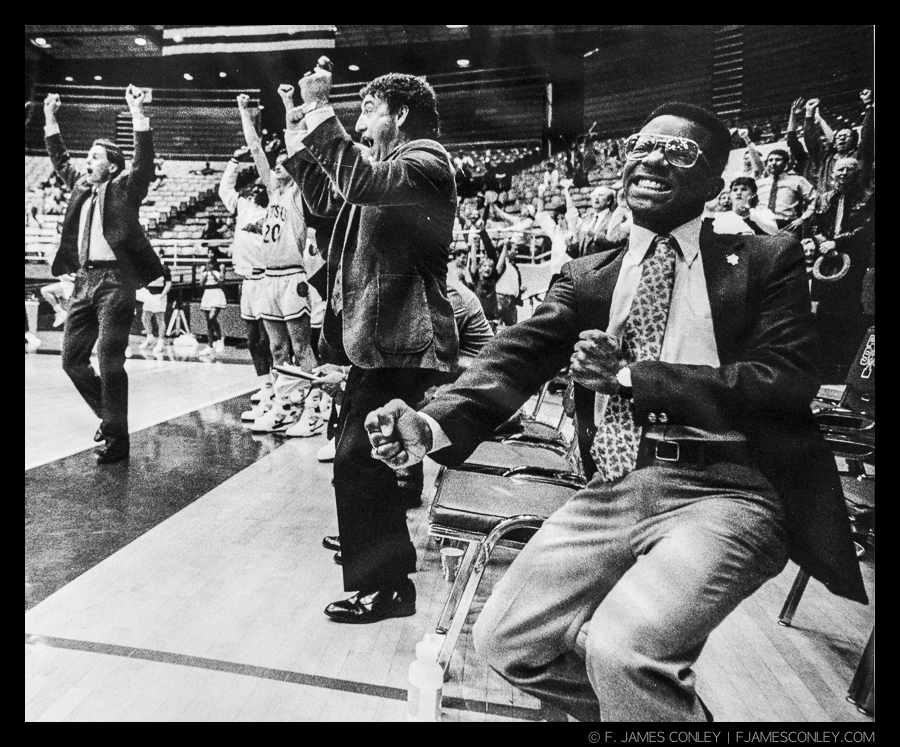

Here are three sports images shot on film (and manual focused, as well). Specifically, with either a Nikon F3 or a Canon F-1n, all on Tri-X pushed to 1600. None of them were shot with a motor drive, because a motor isn't how you find a moment: using your eyes and mind are how you find moments.

If a person is so afraid of missing a moment that the solution is shooting at the maximum speed the camera can record, then that person is taking video. In which case, there are better video cameras than a DSLR or mirrorless camera. And in which case, that person is not seeing moments to capture, but a scene to monitor.

The answer to capturing meaningful pictures is to slow down—not to speed up. Watch, observe, time the moment, and see the picture you're making. Otherwise, you aren't a photographer, you're a videographer, and you're using the wrong tool.

And the winner is? This Sony card comes from a reputable manufacturer, is plenty fast enough, and is relatively inexpensive for its size. For the price, I'd rather have a handful of these cards, which will allow me the freedom to record hundred upon hundreds of individual, meaningful moments, than to to have an expensive card that will absorb 10 frames a second.