I'm embarking on an experiment which will take me back to my roots in photography: one camera, one lens, and black and white film that I'll process myself. I'll be using a Leica M6 with a 35mm lens.

Shooting film is hard. Compared to a modern digital camera, exposure with the Leica is unintuitive. "Focusing" is a goal rather than a consistent possibility. Restricting oneself to a maximum of 36 exposures is a serious limitation (though in a later post I'll talk about why it's a creative answer). Not being able to see in the viewfinder the effect of various camera settings seemingly distances the photographer from the moment.

Despite those difficulties, film is more conducive to the creative process. Making images on film isn't technical: two settings combined with the forgiving dynamic range of silver halide record the image. On the other hand, recording images in digital is highly technical, and good quality images require a lot of consideration of details other than the subject and timing.

With film, the technical aspects are confined to developing and printing. Those aspects are not individual: you won't see a single image until you have a full roll to process. This changes the creative process because the artist is free to (and forced to) think about the project as a whole. The importance of the individual image is diminished, and the message and story become primary again.

Using film demands anticipation and a flow of action which are better suited to draw out creativity. At least, that's the theory I'm putting to the test.

But why a Leica? For anyone familiar with the history of cameras, there are seemingly more reasons to not get a Leica than to get a Leica. Yes, Leica was the first to make 35mm still photography possible, but that's where Leica's innovation began and ended. While Leica's competitors advanced camera technology with zoom lenses, metering, focusing systems, adding more and more features while dropping prices, Leica remained static. Leica has always been materially over built and devoid of features. Leica cameras and lenses are handmade like expensive watches, with equally limited functions and high price tags. The cost of a single piece of Leica equipment is usually close to buying deeply into another system.

Other than price, though, those are all reasons to use a Leica. It's as close to zen as cameras get. The Leica works hard to deprive you of all information other than framing. There is nothing to distract you from the subject, and barely anything to even help you focus. The truth the Leica makes the photographer confront, though, is that no one can at the same time both focus and capture an unfolding moment. Having ground glass focusing screens, autofocus points, or other aides, merely creates time delays while a moment is happening, and distracts the photographer from doing what makes a photograph unique: capturing the moment. By making precise focus a nearly impossible task, the Leica forces the photographer to reorient and give up on trying to achieve it and rely instead on the more relevant concept of zone focusing.

A Leica is all and only about the contents of the image. As Cartier-Bresson described it, a Leica is like a notebook. And in terms of assistance in creating your work, it doesn't offer much more help than a blank piece of paper.

The lack of exposure information in the camera shifts the obligation of attention back to where it belongs: the photographer. (Up until the M5, Leicas had no meter at all. With the M6, the "meter" is merely a couple of arrows. There is no reading of aperture or shutter speed.) It is up to the photographer to manually set the exposure, and because there is no information or reminder about these settings once the camera is at your eye, the photographer must be constantly aware of the scene and how it's changing. There is no "in camera" work--exposure decisions have to be made before the subject is framed. Being forced into making exposure considerations before making framing decisions makes for a richer visual experience, and puts one in touch with the chosen tool.

And the tool is not insignificant. The point of a well made tool is that it diminishes the friction between what you need to do, and doing it. Less is more when it comes to distraction. No matter if it's a Holga or a Leica, the camera matters because the camera contains the set of tools used to create the work. With a Holga, or even a DSLR costing some minimal hundreds of dollars, it is easy to feel a lack of care for the tool because the commodity nature of it is something from which one may naturally resist being associated. The creative problem, however, is that this state of mind creates a distance from the tool. That distance translates into inefficiency in using the tool, and a resulting lack of realized creative potential.

Artificially or not, investing in your tools is a short path to getting in tune with them because it changes the way you think about and handle what you use. Leicas are expensive, and the investment in the thing itself is worth preserving. Continually using the camera while also taking care of it creates a pattern of respect for the tool. Awareness of its operation and foibles translates into more efficient use, which translates into more fluid use, which inevitably leads to better work.

At least, these are the theories. I'll have to report back on how it works in practice!

Shooting film is hard. Compared to a modern digital camera, exposure with the Leica is unintuitive. "Focusing" is a goal rather than a consistent possibility. Restricting oneself to a maximum of 36 exposures is a serious limitation (though in a later post I'll talk about why it's a creative answer). Not being able to see in the viewfinder the effect of various camera settings seemingly distances the photographer from the moment.

Despite those difficulties, film is more conducive to the creative process. Making images on film isn't technical: two settings combined with the forgiving dynamic range of silver halide record the image. On the other hand, recording images in digital is highly technical, and good quality images require a lot of consideration of details other than the subject and timing.

With film, the technical aspects are confined to developing and printing. Those aspects are not individual: you won't see a single image until you have a full roll to process. This changes the creative process because the artist is free to (and forced to) think about the project as a whole. The importance of the individual image is diminished, and the message and story become primary again.

Using film demands anticipation and a flow of action which are better suited to draw out creativity. At least, that's the theory I'm putting to the test.

But why a Leica? For anyone familiar with the history of cameras, there are seemingly more reasons to not get a Leica than to get a Leica. Yes, Leica was the first to make 35mm still photography possible, but that's where Leica's innovation began and ended. While Leica's competitors advanced camera technology with zoom lenses, metering, focusing systems, adding more and more features while dropping prices, Leica remained static. Leica has always been materially over built and devoid of features. Leica cameras and lenses are handmade like expensive watches, with equally limited functions and high price tags. The cost of a single piece of Leica equipment is usually close to buying deeply into another system.

Other than price, though, those are all reasons to use a Leica. It's as close to zen as cameras get. The Leica works hard to deprive you of all information other than framing. There is nothing to distract you from the subject, and barely anything to even help you focus. The truth the Leica makes the photographer confront, though, is that no one can at the same time both focus and capture an unfolding moment. Having ground glass focusing screens, autofocus points, or other aides, merely creates time delays while a moment is happening, and distracts the photographer from doing what makes a photograph unique: capturing the moment. By making precise focus a nearly impossible task, the Leica forces the photographer to reorient and give up on trying to achieve it and rely instead on the more relevant concept of zone focusing.

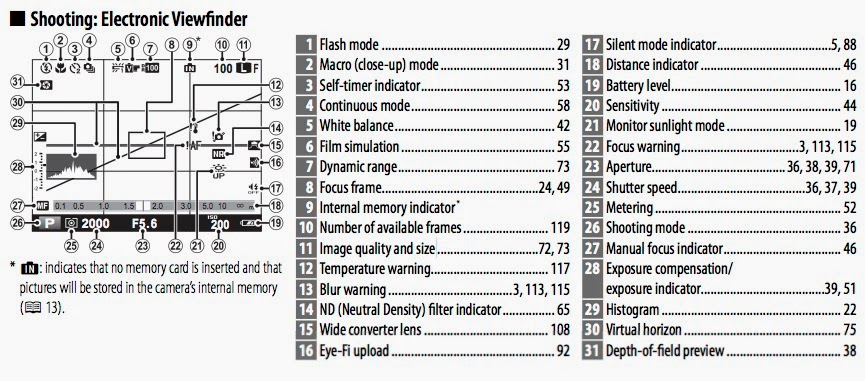

|

| This is the finder information available in my Fuji X100S. Seriously. |

|

| This is the (lack of) information in an M6 viewfinder. |

And the tool is not insignificant. The point of a well made tool is that it diminishes the friction between what you need to do, and doing it. Less is more when it comes to distraction. No matter if it's a Holga or a Leica, the camera matters because the camera contains the set of tools used to create the work. With a Holga, or even a DSLR costing some minimal hundreds of dollars, it is easy to feel a lack of care for the tool because the commodity nature of it is something from which one may naturally resist being associated. The creative problem, however, is that this state of mind creates a distance from the tool. That distance translates into inefficiency in using the tool, and a resulting lack of realized creative potential.

Artificially or not, investing in your tools is a short path to getting in tune with them because it changes the way you think about and handle what you use. Leicas are expensive, and the investment in the thing itself is worth preserving. Continually using the camera while also taking care of it creates a pattern of respect for the tool. Awareness of its operation and foibles translates into more efficient use, which translates into more fluid use, which inevitably leads to better work.

At least, these are the theories. I'll have to report back on how it works in practice!